Introduction

- In September Penny and I followed the famed, and for many centuries sought after, route through Canada’s Northwest Passage. We did it in style and only in three weeks, as opposed to the arduous journeys of many months, and in most cases years, that the early explorers took.

- For a broader selection of my photos than shown in this Blog, go to: https://photos.app.goo.gl/FpwKPMPdFb9fJSKM8

- We joined an Adventure Canada trip on a ship that navigated its way through the Northwest Passage from the west to the east. It started in Kugluktuk, located at the mouth of the Coppermine River, on the Coronation Gulf.

- Our journey took us 5,000 kms over 2 1/2 weeks, through three time zones, from the western Arctic through the Northwest Passage to Greenland; down the Greenland coast and flight back from the town of Kangerlussuaq. We reached a maximum latitude of 75’ 56N on September !8 in Kap York, Greenland. At that point we were 1,626 kilometres (924 miles) north of the Arctic Circle. We crossed the Arctic Circle twice and were above it for most of the journey.

- We were awakened, educated, organized, boated, fed, guarded (from Polar bears) and entertained by both the staff of Adventure Canada as well the ship’s cadre of waiters, cooks, bartenders, room attendants, and of course navigators and operators of the Ocean Endeavour, an ice reinforced ship built in Poland in 1982. It is 137 metres (450’) long with a 21 metre (69’) beam and a 5.8 metre (19’) draft. A ship’s crew of 124, with 35 Adventure Canada staff ran the operation.

- There were 194 passengers on the journey, with around 35 associated with Canoe North Adventures (owned and operated by Al Pace and Lin Ward), i.e. the booking was sold through them. Seven of this group were from Peterborough or Stony Lake (Don Harterre, Gail Martin, Val and John McRae, Priscilla Brooks-Hill plus Penny and me).

- Adventure Canada were well organized in moving us around – into Zodiacs primarily, as well as at meal times. So everyone was assigned to one of six colour groups, and that group would follow the directions we were given. We were scanned, like groceries at Loblaws, on and off the boat.

- We were all assigned tables, and table mates, that turned out to be for the whole trip. This was a COVID related protocol so mixing up was not possible. It was too bad, as that is one of the delights of this kind of travel.

- Our own room choice turned our to be an excellent one: a bedroom, sitting room, two bathrooms and two portholes with an unrestricted view out. Two TV screens delivered the daily agenda plus a selection of Arctic related films.

- The ship had a gym, hot tub, sauna, library, gift shop, massage therapist, yoga; as well there were kayaks available. A Polar dip was carried out in the pool near the end (Penny and I were voyeurs).

- The ship had 20 Zodiacs, which are rubber, rigid-hulled, inflatable boats. They are stable, handle easily, maneuverable and generally took around 10 passengers.

- Whenever we headed out in the Zodiacs, and then onto the land, we had a routine – go to our lockers and get on a life jacket, and if it was a wet landing (essentially no dock) put on the rubber boots we were issued. The other routine was not to venture outside a perimeter set up around each of our land ventures; staff with guns were there to keep us safe from hungry Polar bears.

- Excellent dining with usually three main course choices; freshly prepared desserts; afternoon tea with baked cookies. We chose an unlimited wine package plus the cocktail of the day ($600) for us both; we got our money’s worth.

- A few of the staff were talented musicians; some evenings we listened to them sing and play.

- There was anxiety getting on board, namely in passing the COVID testing, the first administered in Peterborough – a PCR test done a few days before we flew west. Then again, once we arrived in Yellowknife, an antigen test was given. COVID changed the experience somewhat, as caution was being exercised by the operator. So we wore masks at all inside gatherings – in the dining room (unless eating), in the lecture rooms and even on the many Zodiacs trips we took. It was worth it as no cases of COVID emerged until day 13, when a group of passengers came down. In total 11 passengers had to isolate (two of our seven Peterborough cadre) in their rooms and were not able to fly back on the charter from Greenland. (As a photographer I hate the mask; it dehumanizes and disguises personalities and emotion.)

- Our days were busy. Adventure Canada had a large staff, representing the many areas that they felt were important for us to learn about or experience in this unusual journey. Lectures were provided by some very knowledgable and experienced people. Their subjects included animals, birds, cetaceans (including the different whales), explorers (and in particular the famous Franklin expedition), ethnobiology, archaeology, geology, geography, polynyas, sea ice mapping, glaciers, Inuit culture and politics, Arctic sovereignty, the innards of the ship, photography, Greenland – and more.

- Flowers, while at their most frenzied in July, are still around to see, in their miniaturized, slow-growing Arctic state.

- The sea delivered whales: bowheads; belugas and narwhals continue to migrate in August and September, as well four other types were sighted; seals, mostly harp and ringed, and walrus made their appearance.

- The birders count reached 23 different species.

- Animals: we learned a lot about what the Arctic supports. Some were spotted and photographed (Polar bears, muskox, caribou, Arctic fox, Arctic hare, Arctic ground squirrel).

- Near the end of the trip we were presented with a pretty good show of Northern Lights.

Itinerary

Here is our daily itinerary, including what and where we were, and what we did:

Wednesday, Sept 7: Air North, Toronto to Yellowknife on the banks of Great Slave Lake; stayed at Explorers Hotel; dinner at the funky Bullocks Bistro.

Thursday, Sept 8: walked along Ragged Ass Road into Old Town; looked out at the colourful floating houses in the bay; rapid antigen test; ArriveCan app (grimace); lecture; Trader’s Grill for dinner.

Day 1, Friday, Sept 9: charter flight to Kugluktuk.

*What and where we were: the town is located at the mouth of the Coppermine River, on the Coronation Gulf, southwest of Victoria Island. It is near the border with the Northwest Territories; the western-most community in Nunavut.

* What we did: flight took 1 hour and 20 minutes. We were bussed to a dock and then on to a Zodiac to board ship – the Ocean Endeavour. Life jacket drill. Dinner with Al Pace and Lin Ward (and for rest of trip).

Day 2, Saturday, Sept 10: Port Epworth.

* What and where we were: Port Epworth is a future UNESCO World Heritage site. It’s on the south shore of Coronation Gulf (the mainland) in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut; Victoria Island is to the north. We continued east through Dease Strait.

* What we did: we reached this site by Zodiac. When we learned that there are rocks here called stromatolites (fossil bacterial colonies) that lived at the ocean bottom of shallow warm seas 1.9 billion years ago, it was an incredible realization. The geological significance of this is enormous in terms of the early evolution of life on our planet. We could see and touch the petrified remains of primordial mounds of algae, formed during the dawning days of life nearly two billion years ago by the very organisms responsible for producing the oxygen we breathe today.

We hiked around the area and received our first exposure to the tiny flowers and lichen of the North’s short growing season. The terrain was tundra, littered with erratic boulders, and slowly eroding sedimentary rocks and outcroppings teeming with ground plants (bearberry plants and bear scat filled with the seeds, tiny willow trees inches high, Arctic bell heather, dwarf fireweed, moss campion, etc.)

Back on the ship two lectures got us started: “An Introduction to the Archaeology of Arctic Canada & Greenland” (Liz Robertson) and “All of it About Nunavut” (Aaron Spitzer). Then the Inuit staff demonstrated their ritual of lighting the kudlik (or the qulliq), the traditional seal oil lamp that provided light and warmth (as well as melting snow, cooking, and drying clothes) in the harsh Arctic environment where there is no wood.

Day 3, Sunday, Sept 11: a sea day as we enter Queen Maude Gulf.

*What and where we were: the Royal Geographic Islands are to the north, guarding the gulf from the inflow of dangerous Arctic pack-ice pressing down from Melville Sound to the north. It is quite wide and open. We are headed for the Boothia Peninsula, King William Island (which was, it was pointed out in a lecture, key to the Northwest Passage) and southern part of Prince of Wales Island (where Franklin’s ships were found).

* What we did: listened to presentations on: Arctic wildlife and their remarkable adaptations (Ree Brennin-Houston); photography (Dennis Minty); “The Amazing Discovery of the Erebus and Terror – the Misadventures of the Northwest Passage” (Aaron Spitzer); Arctic plants – the highs and lows (Dawn Bazely; “We’re in a cold desert called the tundra”; “50% of all plants are trees, but in the Arctic it’s almost zero”). Penny and I bought a soap stone carving of a walrus from a sculptor from Umingmaktok. (It is said that when we hold a handmade carving such as this we are in touch with the landscape – and I agree.) Then I got an excellent massage.

Day 4, Monday, Sept 12: Gjoa Haven.

* What and where we were: this is a small Inuit village on the south shore of King William Island, Nunavut. Its population is 1,500, and its Inuit name is Uqsuquuq, i.e. a name I note that has 4 “u”s, 3 “q”s and only one other letter, an “s”! (The name means “lots of fat”.) It’s named after Roald Amundsen’s ship the Gjoa. Amundsen spent two winters in this harbour (he called it “the finest little harbour in the world”) in 1901-03 and went on to complete the first transit of the Northwest Passage in 1905.

* What we did: Zodiac ride in to the town and walked around visiting the city council hall, the hotel, grocery store, the museum and Nattilik Heritage Centre. The Ullulaq Inuit Arts Gallery is housed in the Centre. I purchased a soap stone mask and Penny an Arctic fox sunburst-shaped parka hood, or puhitaq. The town will be the centre for Inuit guardians hired and trained by Parks Canada to patrol the national historic site of the Franklin shipwrecks, the HMS Erebus and Terror. This is the first national historic site to be co-managed by Parks Canada and Inuit in Nunavut.

There were two lectures in the afternoon: “What Really Killed Those Franklin Dudes” (Liz Robertson) and “Past, Present, and Future of Inuit Nunangat” (Randy, Sheila Flaherty). The term “Inuit Nunangat” is a Canadian Inuit term that includes land, water, and ice. Inuit consider the land, water and ice, of their homeland to be integral to their culture and way of life.

Day 5, Tuesday, Sept 13: Prince of Wales Island.

* What and where we were: after leaving Gjoa Haven we sailed through Rae Strait and after that the James Ross Strait – both on the east side of King William Island. This passage is rich in marine and avian life.

* What we did: morning talks on rocks (Lynn Moorman) and the ecology of glaciers (Clement Weisleitner); we then took a two hour Zodiac ride on a very overcast and drizzly day. Five polar bears were spotted as we were cruising in Coningham Bay on Prince of Wales Island off Franklin Strait. One was lying down for a bit, and another eating perhaps a seal; good photo opps. Hot chocolate and Bailey’s with the kayakers as we returned to the ship – as it was chilly. Saw the Canadian Coast Guard ship the Pierre Radisson. The land so far is flat, stark and bleak, yet alluring.

Day 6, Wednesday, Sept 14: through Bellot Strait and landing at Fort Ross.

* What and where we were: the Bellot Strait is 32 kilometres long and two kilometres wide. The north side of the strait rises steeply to approximately 450 metres, and the south shore to approximately 750 metres – It separates Somerset Island from the Boothia Peninsula. Here the first meeting occurs of the Atlantic and Pacific tides north of Magellan Strait at the tip of South America. At roughly it’s midpoint, the strait passes the northernmost extent of the North American mainland, the tip of the Boothia Peninsula. A sledge party from one of the search expeditions for Franklin (William Kennedy in command) discovered the narrow passage in 1851.

At one point there’s a submerged rock (Magpie Rock) on one side and shoal on the other, leaving a channel no more than 400m wide. At this point the current reaches 8 knots so you must go with the tide and there’s no turning around once you’re in there! The strait is described as the “ancient basement of the earth as the rocks come from 5 kms down”. Once through the Bellot Strait, and our visit to Fort Ross, we headed north up the Prince Regent Inlet (Peel Sound & Parry Channel).

What we did: after navigating the strait, with its steep hills making for wonderful views, we visited the historic site Fort Ross on its eastern edge. It is an old Hudson Bay Trading Post that was established in 1937 – one of the last and most remote they built. We hiked around the area and visited the two buildings that remain – the manager’s house and the store. It only operated for 11 years and was abandoned because the ice constantly choked the strait and severely hampered the resupply ship. What a lonely, desolate place. Pictures of tiny flowers plus a dead fox.

James Raffan gave a lecture on polar bears (you must read his great little book Ice Walker). Through Dennis Minty, the Nikon professional on board and photography lecturer, I borrowed the Nikon 200-500 mm lens; quite large and heavy but sharp, right out to its full telephoto length.

We learned today that we won’t be making it up to Gris Fiord on Ellesmere Island as their bay is closing in with ice and the weather deteriorating; if we did get in, there was no guarantee that we could get out in a reasonable period of time. (It is 1,150 kms above the Arctic Circle, Canada’s northernmost “civilian” community. In 1953, Inuit were relocated there by government under false pretences, to assert Canadian sovereignty.)

Day 7, Thursday, Sept 15: Beechey Island: Graves and Northumberland House.

* What and where we were: Beechey Island is the holy of holies from a historical point of view. It is where Franklin overwintered in 1845 and the graves of three of his men are there (they died early 1846). Thomas Morgan of HMS Investigator was also buried here in 1854 beside the three graves.

* What we did: before reaching Beechey, and early in the morning, we passed by Prince Leopold Island, noted for its extraordinary bird cliffs that house thick-billed murres, northern fulmars, and black-legged kittiwakes. We then heard about “the bizarre and beloved Narwhal” from Deanna Leonard-Spitzer and the “science of the Franklin lost” (Liz Robertson). After a Zodiac ride to the beach at Beechey we walked around the graves.

We then hiked about 2 kms to the ruins of Northumberland House, built in 1850. The island became the de facto base for future Franklin searches. Found a pretty Arctic poppy that apparently follows the sun, much the way sunflowers do further south; this maximizes heat collection for their reproductive process.

Day 8, Friday, Sept 16: cruise down Lancaster Sound and Devon Island.

* What and where we were: this point marks the demarcation of what is really the true Arctic. North of here very few Inuit live, as it’s very harsh, cold and has little game. As of 2017, the boundary for the Lancaster Sound National Marine Conservation Area (or Tallurutiup Imanga) is now connected to Sirmilik National Park, the Prince Leopold Island Migratory Bird Sanctuary and the Nirjutiqavvik National Wildlife Area which brings the total protected area to be over 131,000 square kilometres. This is an area about the size of Greece. The area is a critical habitat for the Canadian Arctic’s largest density of polar bears, 75% of the global population of narwhals, 20% of Canada’s beluga population, along with ringed, harp and bearded seals, walruses, and bowhead whales. One third of Canada’s colonial seabirds feed and breed in the area.

* What we did: we cruised east along Lancaster Sound and poked into two large bays – Stratton Inlet and Burnett Inlet on the south shore of Devon Island, which is the largest uninhabited island on the Earth. The island’s surface is similar to that of the moon! We then went into Powell Inlet and saw herds of seals, of walrus and a pod of the ghostly white beluga whale.

Dave Garrow’s tale of dragging a 140 pound sled for many days by skiing to the North Water Polyna (The Great Upwelling) was amazing and crazy. Our Inuit staff, John, Sheila, Johny, Susie, Joe, Randy and Aka served us a “country food tasting” on the back deck. We tried raw Arctic char, minke, whale skin (mattak), muskox, walrus, caribou (tuktu), seal.

Day 9, Saturday, Sept 17: crossed Baffin Bay.

* What and where we were: we leave Canada for Greenland across Baffin Bay. This huge bay, located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is a marginal sea of the North Atlantic Ocean. It is connected to the Atlantic via the Davis Strait and the Labrador Sea. The narrower Nares Strait connects Baffin Bay with the Atlantic Ocean. The bay is not navigable most of the year because of the ice cover and high density of floating ice and icebergs in the open areas.

* What we did: most of the day was taken up with lectures or workshops. In the morning Ree Brennin-Houston gave a lecture on “Beluga Whales: Canaries of the Sea”; Deanna Leonard-Spitzer gave a talk in the afternoon on “Marine Mammals of the Arctic”. I spent an hour with James Raffan on “Journal Keeping 101”. Penny did a beading session with Susie, Sheila and Aka. The sea was heavy, rising to around four metres; some spent the day in their cabins as a result.

Day 10, Sunday, Sept 18: Melville Bay and hike at Kap York on Greenland.

* What and where we were: Kap York is an important landmark delimiting the northernmost boundary of Melville Bay. During the whaling era, Melville Bay was dubbed “the wrecking yard” due to the disproportionate number of wooden ships crushed by the ice during the annual whaling season in north Davis Strait. In 1818 explorer John Ross became the first Westerner to meet the Inuit of the Far North, the Inughuit or Polar Inuit.

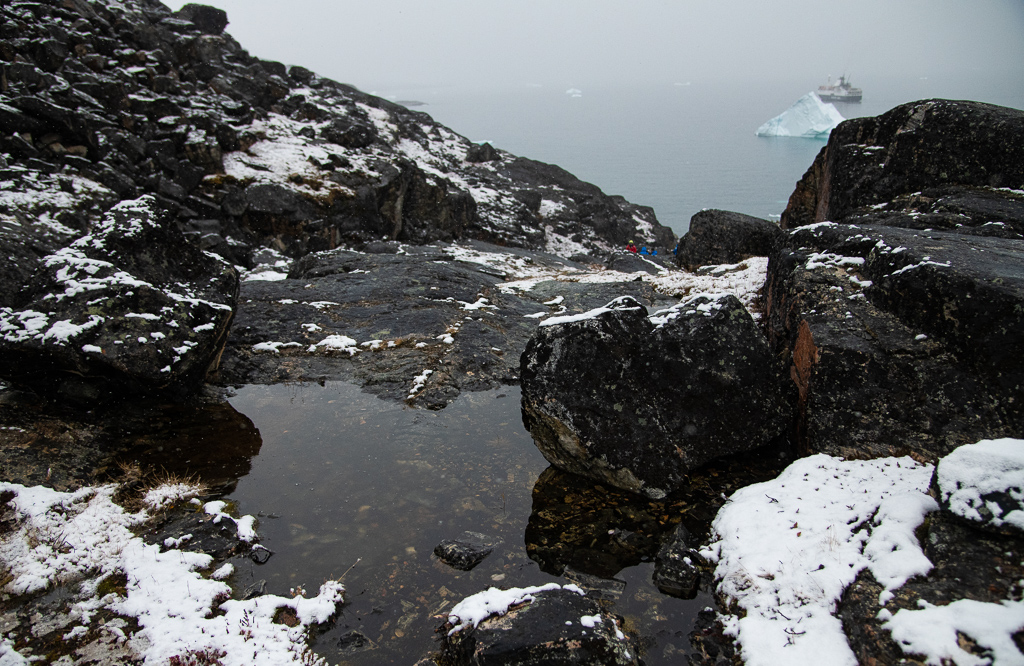

* What we did: we stared in amazement at the icebergs that are everywhere – very beautiful. Dovekies cling to the rocks of the cliffs. Wet landing at Kap York in the Zodiacs on a rough flat area with high cliffs in background and small little ponds and rivers coated with gloss-like ice. Rough walking but beautiful.

Back on ship and watched it navigate what they call iceberg alley – hundreds of different shaped icebergs everywhere.

Lectures on Arctic sovereignty (Aaron Spitzer), “My Greenland” (Aka) and seabirds (Dennis Minty). Five more cases of COVID today go with the two yesterday; things are battened down again with masks obligatory inside and on the Zodiacs.

Day 11, Monday, Sept 19: hike at Upernavik.

* What and where we were: the Upernavik Archipelago is a vast coastal archipelago in northwestern Greenland. It belongs to the earliest settled areas of Greenland, the first migrants arriving approximately 2,000 BCE. All southbound migrations of the Inuit passed through this area, leaving a trail of archeological sites. The early Saqqaq culture diminished in importance around 1,000 BCE, followed by the migrants of Dorset culture, who spread alongside the coast of Baffin Bay, being in turn displaced by the Thule people in the 13th and 14th centuries. The area has been continuously inhabited since then.

* What we did: took a long overnight cruise down the Greenland coast; it was foggy and overcast. Listened to a lecture by James Raffan “Circling the Midnight Sun” (buy his book by that title – that’s now two plugs for Raffan!) and one by Lynn Moorman “Too Cool! Glaciers and Sea Ice”. In the afternoon we went on a four hour hike across terrain that was quite a challenge for my gimpy knee: hilly, boggy, irregular rocks, no real path, in a drizzle, while at the same time parts of the tundra felt like a soft, thick carpet of peat. We reached a sod house circa 1700s plus a rocky structure believed to be a meat cairn with a large bowhead whale bone stuck inside it.

Got pics of Sheila Flaherty picking Arctic Willow plants (has edible leaves; roots can be chewed to relieve a toothache; is very high in Vitamin C; the decayed flowers are mixed with moss and used as wicking in the kudlik) with a wonderful rugged background. Deserved a long shower and “drink of the day” upon return. Certainly getting to know the bartender. (This delightful chap has three wives, and a child with each of them, living in three different countries.)

Day 12, Tuesday, Sept 20: Uummannaq Bay; Store Glacier.

* What and where we were: we passed the community of Uminak but it’s too foggy to make out much and moved on to anchor in Uummannaq Bay.

* What we did: there’s a low ceiling but some interesting light. I headed out with Dennis Minty in a Zodiac photographing the icebergs and two fishing boats doing their thing in the bay. Staff from the ship’s kitchen brought 150 pounds of fresh halibut from one of them; it melted in your mouth that night for dinner. Glaucous gulls (the second biggest gull in the world) hovered around the boats; a lonely waterfall was in the distance. Back on the ship – a lecture on plants (Dawn Bazely).

The early evening turned into one of those special moments. The captain brought the ship deeper into the fjord, closer to the huge Store Glacier. (The glacier is 5.5 kms wide at its front-end and is ranked 2cd or 3rd in iceberg discharge for west Greenland. It is remarkably stable and is heavily grounded.) The way in was blocked by ice though, so we couldn’t get that far down. But the light was dramatic – both dark and bright, with shadows and late sun bouncing off the land in the distance and the incredible array of ice bergs and bergy bits surrounding the ship.

I like the morning quotes: “A journey is like a person – there are no two alike.” “You don’t take a journey – a journey takes you.”

Day 13, Wednesday, Sept 21: Qilakitsoq; Uummannaq.

* What and where we were: we are still 1000 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle, and midway up Greenland’s west coast. The landscape is dominated by the twin peaks of the 1,170 metre high granite mountain called Uummannaq (also the name of the village) that occupies almost the entire northern half of the island.

Opposite the island is the famous archaeological site of Qilakitsoq, where the Greenland Mummies were found. This dates from around 1475 where the mummified corpses of six women plus a six month baby girl and four-year old boy were found in a cavern on a steep cliff. They were cushioned and covered with sealskins, flat stones, and grass. All were buried with their clothes on along with their tools. It is speculated they died of some food poisoning while their husbands were out hunting. The area is moon-like; it’s in a small bay off the ocean, with small icebergs swirling around the end of the bay.

* What we did: we hiked up a quite steep slippery trail full of loose rocks, mud, grasses – and somewhat treacherous as it was raining. At a certain point there appeared the remains of a stone cairn and hut where the Thule Inuit lived. The grave was located beneath an overhanging cliff and consists of a pile of large stones, as was usual due to a lack of suitable soil. Some 53 graves have been found in this area plus eight sod huts.

Once back on the ship we cruised around to the other side of the peninsula where there is the small (1,400) village of Uummannaq. After lunch we visited this village and took in the blubber house, church, museum and an orphanage. A local showed us the dogsled (komatik) he uses to travel hunting in the winter. We listened to six women ages around 16 to 30 plus a four year old girl sing traditional songs and play their drums.

COVID hit Val (and then John the next day) McRae, so into isolation. We didn’t see them again (on the trip, that is)!

Day 14, Thursday, Sept 22: cruise through Disko Fjord.

*What and where we were: this area is the source of many of the icebergs that threaten the shipping lanes to the south. It is the largest open bay in western Greenland measuring 150 kms east to west and has an average depth of 400 metres.

* What we did: in the morning we had a spectacular sail through this fjord. Growlers and bergy bits floated in the bay along with hundreds of larger icebergs. In the afternoon I headed out with Dennis Minty and the photography group, but broke away after a bit as there were some interesting close-up opportunities that take time to do (jelly fish, small rivers, shells, small flowers).

A presentation on “Living and Learning With the Sea Ice” by the Inuit staff made the point “Ice is our hope. It’s sad how conditions have changed. We can work in water – but only when it’s frozen.” I was impressed with another presentation by Scott McDougall entitled “A Case for Climate Hope and Optimism”. It should be canned and distributed widely. I also enjoyed the presentation on Fritdjof Nansen (by Alex Preston) as well as “When 3 Words Collide: Dorset, Thule and Norse.” (Liz Robertson).

Day 15, Friday, Sept 23: Qeqertarsuaq, Disko Island.

* What and where we were: out for a Zodiac cruise in the morning. A change of plans has occurred as ice has jammed into the Ilulissat harbour; it might take us 1 1/2 hours to get in and we might not get out. So we weighed anchor and headed further south to the nearby town of Qeqertarsuaq. This is about 250 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle (and just south of where the Greenland icecap reaches the sea at the Ilulissat Icefjord. We were to see the Sermeq Kujalleq Glacier, one of the most active and fast moving in the world – it calves more than 35 cubic kilometres of icebergs annually). The west Greenland coastline is a mixture of fishing villages, islands and coastal waterways.

Qeqertarsuaq is a small seaport and is the main town of Disko Island. The town is one of the oldest settlements in Greenland. It was founded by whalers in 1773, but archeological findings show that there used to be a settlement here some 4,000 years ago. The town serves as the administrative centre for North Greenland. It has a campus for the University of Copenhagen, a museum, meat market, power plant and a lovely waterfall.

What we did: headed out early on wet and chilly Zodiac ride amongst the icebergs, some nearly 100’ high. Big waves made getting into and out of the craft tricky.

In the afternoon we walked around the town of Qeqertarsuaq: out to their famous black sand beach (it’s Greenland’s only volcanic region), and then past the cemetery to their soccer field dominated by a backdrop of icebergs hovering quite close in – quite a contrast to the field’s very green artificial turf. The vegetation is lush, and the Arctic autumn means foliage is in colour. Met two delightful young Greenland girls around 12 or 13 who wanted to practice their English. In the rain my camera strap slipped off my neck and my 24-120 mm lens was damaged.

In the evening a great concert with the ship board musical talent, featuring Barney Bentall and “friends”. (Barney is a Canadian pop/rock singer-songwriter who is most well known for his 1990s-era band, Barney Bentall and the Legendary Hearts.)

Day 16, Saturday, Sept 24: Sisimut.

* What and where we were: Sisimut is the second largest city in Greenland, after the capital Nuuk. It’s still 75 kilometres above the Arctic Circle. Architecturally, it is a mixture of traditional single family houses and communal housing, with apartment blocks raised in the 1960s during a period of expansion in Greenland.

* What we did: in our morning briefing we learned that we reached 1826 kilometres above the Arctic Circle on this trip, and we have travelled almost 5,000 kilometres. James Raffan provided his insights in his “Idea of North” and Deanna Leonard-Spitzer gave a presentation on whales (“It’s a super marine mammal”).

We took our Zodiacs to the dock at Sisimut and wandered around. The town is colourful and clean; lots of dogs, mostly tied up. Into the local hotel for a sampling of Greenland delicacies. I liked the reindeer sausage, the caplin (smelt), and the shrimp. We visited the oldest standing church in Greenland, built in 1775.

Back on the boat a good display of Northern lights was presented to us around midnight.

Day 17, Sunday, Sept 25: sail up Søndre Strømfjord; Kangerlussuaq; flight to Toronto.

* What and where we were: this 190-kilometre fjord is one of the longest fjords in the world and is framed by dramatic, glacial-carved mountains. Although the fjord crosses the Arctic Circle, like the oceans here it does not freeze. Locals can thank ocean currents for this, making this part of Greenland an open water centre for whaling and fishing all year. The town of Kangerlussuaqa at the eastern head was a former US airforce base.

* What we did: as we cruised up the fjord, all manner of final preps were taking place for our departure from the ship: bags packed and out, tips dispensed, a farewell gathering in the Nautilus Lounge including songs and photos of the journey, and good-byes delivered. A bus to the airport; a final snort at the ArriveCan app and we caught our charter flight back to Toronto. It took over four hours on a large Airbus A330-300 one third full operated by Hi Fly (I hoped the pilots weren’t!)

Tidbits learned; a final recap:

- The Arctic is characterized by grand expansive spaces and huge vistas with few marks of man. It has a raw, austere nature – like some of the Arctic canvases painted by Lawren Harris. Normal references to size are often absent, so a cliff or iceberg or island leaves one puzzled as to scale. It’s a monochromatic experience, with whites and greys of various tones. That’s why the light dashes of colour in the small plants are so welcome

- Being surrounded by ice, animals and an extremely unforgiving, rugged, remote country inspires awe and some trepidation. The absence of background noise (depending on the wind) forces one to recalibrate to the silence. The absence of civilization in much of where we have been, to the realization that it’s rare to even see the contrails of a jet passing overhead, means the beaten path isn’t where we are!

- The word “Arctic” comes from the Greek arktos (bear) for the region lies below the constellation of the Great Bear. Some called it the roof of the world; others called it terra incognita, the unknown land, or ultima Thule, the remote north

- There is little precipitation, thus the Arctic is known as a “polar desert”; the Arctic, and the Antarctic, are the coldest places on the earth

- Weather dominates all; one has to be “weather flexible” in the far North (witness at least two major recalibrations in our journey)

- Strong winds, called katabatics, can develop; things can change quickly

- Mirages can occur (called Fata Morgana) which trick the eye into seeing an island (or mountain) with a faint shimmering at its edges that is not really there. I have photos of such an incident (apparently they happen because rays of light bend when they pass through air layers of different temperatures in a steep thermal inversion)

- The inhabitants: the Arctic contains some of the oldest of man’s ancestors. There has been a diverse Native people for thousands of years. In the Arctic and Greenland they are called Inuit (people). The singular is Inuk (person). In Alaska they are Inupiat; in the Mackenzie River delta, they are Inuvialuit. In the past they were all called Esquimaux or Eskimo, a name given to them by their southern Indian neighbours

- Ten major groups of Inuit lived in the Canadian Arctic (by the time Europeans began arriving); all spoke Inuktitut. Most of their tools and clothing were made from the hides, skins, gut, sinews and bones of the animals they hunted

- Inuit key to survival was proper clothing – elaborate, multilayered, made from skins of caribou, polar bear, Arctic fox, dogs, seals and some birds, that conserved body heat, insulated the wearer, controlled humidity, prevented a buildup of internal temperature and was also waterproof; domesticated dogs and the dogsled (komatik) which was built to be flexible to bend and give over the uneven surface with long runners coated with mud (that when frozen glided over ice with ease); lightweight watercraft (umiak or large boat for whaling for 10 to 20 people; plus the smaller kayak); weapons adapted to hunting both game and sea mammals (built-up bows made of pieces of wood lashed together and reinforced with sinew; lances, spears and harpoons with detachable toggled heads). Most explorers didn’t adapt and wore wool that would overheat, and the perspiration froze (it “became their shroud”). A handful of explorers adapted (John Rae, Roald Amunsden, Francis McClintock for example.)

- Inuit food: raw food (seal liver, blubber and meat, as well as whale) provided essential nutrients and vitamins, particularly C; blood soup; partially digested plants or shrimp from the stomachs of birds and animals. Also the practice of sharing food runs deep in Inuit culture. A cultural aside: it seems that the Inuit want the means to hunt for the food they’ve always lived on. But there is a growing problem regarding access to affordable, nutritious food. The high prices are startling on the food items we saw in the grocery stores we visited; this was attributed to the high shipping costs to communities that have no highway access.

- Inuit shelter: skin tents in summer; the igloo in winter

- The Inuit had an intricate system of belief, superstition and ritual to help them survive and to explain things

- Solid ice covers about 6,000,000 square kilometres of the Arctic Ocean. Nearly half the surface of the water that does remain open is filled with ice floes. The ice generally drifts southward and eastward, and some of it is carried out into the Atlantic. The Beaufort Sea has the heaviest concentration of ice, and the gathering place for many ice floes

- Polynyas are areas in the Arctic that never freeze over (for complicated reasons). They are a critical food source for a variety of organisms such as fish, birds, and marine mammals

- Only 10% of the Arctic waters have been surveyed/charted

- Very ancient rock systems are present, e.g. the stromatolites we saw in Port Epworth are 1.9 billion years old

- Has few species but within those species there may be large populations (millions of seals, hundreds of thousands of caribou, walruses and whales. Victoria and Banks Islands host over 80,000 muskoxen)

- Whales: grays, finbacks, bowheads + two unusual ones: the ghostly white beluga and the long-toothed narwhal. Greenland also has minke, killer, pilot, right, and humpback (they migrate out of Arctic in winter). They are cetaceans, along with dolphins and porpoises. Bowheads can stay under the ice all winter long; they over-winter in polynyas

- The majority of the world’s sea birds live at least a part of the year in the north polar region. Arctic terns are “superstars” (they summer in the Antarctic for goodness sake!). Others include: northern fulmar, snow bunting, common eider, ptarmigan, kittiwake, black guillemot, glaucous gull, red-throated loons, etc., etc.

- There are insects (spiders, beetles, flies, mosquitoes)

- There are two groups of animals: those that live year round (polar bear, muskox, caribou, Arctic hare, Arctic fox, collared lemming; ground squirrel – the only animal in Arctic that hibernates!) and those that visit during the brief summer (wolverine; weasel)

- We saw (or on occasion thought we saw in the case of the muskox) what are considered the Arctic’s “big five”: polar bear, muskox, narwhal, beluga, walrus

- We learned about polar bears: did you know that they have been seen swimming for more than a week straight and clocking over 400 miles; have large furry feet; swim using only front feet; have 2,100 times more acuity in their scent?

- Many Arctic animals are white (Polar bears, beluga whales, Arctic fox, gulls, etc.)

- The area is rich with plant life (2,000 varieties of lichens, 500 types of moss, 1,000 other plant species; there is lots of plankton which the fish feed on and in turn are eaten by ringed seals or walrus); much of the land is permafrost, or soil permanently frozen to a rock-hard consistency. Lichens get their nutrients from the rocks they populate. Berry plants, such as blueberry, mountain cranberry, and crowberry disperse their seeds by enclosing them in juicy, sweet globes, that are appetizing for animals. After being eaten, many seeds are not digested and are deposited in the excrement some distance away from the parent plant

- Arctic ecosystems are the youngest on earth – only about ten to twelve thousand years old, which is much younger than Homo sapiens. Most land life in the Arctic was eliminated during the last glaciation, so current plant communities have only been able to establish themselves since the big melt

- Arctic plants grow low to take advantage of the warmer temperatures and more gentle wind. It’s a short growing season

- Occasionally little bits of colour sneak in, in the guise of some lovely little miniature plant or lichen that provide a subtle dash of red or orange or a muted green/brown appearance

- The Arctic eco-system is changing, and faster than any other water body on Earth: it is thought that a great many species are yet to be discovered; the water is 33% less salty than in 2003 and 30% more acidic; the Beaufort Gyre, a vast, circular current that has alternated direction every decade, hasn’t switched in 19 years; nutrient-rich water from the Pacific isn’t getting mixed in as it used to, which affects the plankton blooms that anchor the Arctic food web; sea ice is shrinking and thinning (affecting ability of Inuit access to hunting grounds); erosion has doubled in past few decades and will worsen as wave height is projected to increase with the giant lid of sea ice gone; species mix is changing (more killer whales, Pacific salmon, capelin and harp seals moving up); increased shipping (noise). Glaciers are losing more mass than they gain

- There was a four century quest for a Northwest Passage. I’ve written a separate blog about the impact 400 years of European exploration searching for a Northwest Passage. I call it “Civilizations Collide in Extreme Conditions in the Search for a Northwest Passage”, and it can be found at: https://powellponderings.com/civilizations-collide-in-extreme-conditions-in-the-search-for-a-northwest-passage/

Back-up documents

- Of course, we learned a lot about the geography, as well as Greenland, and also the explorers who for 400 years attempted to find a passage through. For a summary of the attempts in searching for a passage, see Attachment #1: Key Arctic Explorers – the European Quest for a Northwest Passage in the Arctic Ocean. Here is the link as it is a longer document: https://powellponderings.com/attachment-1-key-arctic-explorers/

- For some information on the geography of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago see Attachment #2 and for information about Greenland see Attachment #3, both at the bottom, as part of this blog.

- For a link to a number of photographs of the trip, go to: https://photos.app.goo.gl/FpwKPMPdFb9fJSKM8 My Thanks to Jan Hauck for her photos of the Arctic fox, and the waterfall.

Attachment #2: Geography of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago

- The Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland.

- The archipelago extends some 2,400 km (1,500 mi) longitudinally and 1,900 km (1,200 mi) from the mainland to Cape Columbia, the northernmost point on Ellesmere Island. (It is also the world’s northernmost point of land outside Greenland. The distance to the North Pole is 769 km.) It is bounded on the west by the Beaufort Sea; on the northwest by the Arctic Ocean; on the east by Greenland, Baffin Bay and Davis Strait; and on the south by Hudson Bay and the Canadian mainland.

- The various islands are separated from each other and the continental mainland by a series of waterways collectively known as the Northwest Passage. Two large peninsulas, Boothia and Melville, extend northward from the mainland. The northernmost cluster of islands, including Ellesmere Island, is known as the Queen Elizabeth Islands (and was formerly the Parry Islands).

- The archipelago consists of 36,563 islands, of which 94 are classified as major islands, being larger than 130 km2 (50 sq mi), and cover a total area of 1,400,000 km2 (540,000 sq mi).

- After Greenland, the archipelago is the world’s largest high-Arctic land area. The climate of the islands is Arctic, and the terrain consists of tundra except in mountainous regions. Most of the islands are uninhabited; human settlement is extremely thin and scattered, being mainly coastal Inuit settlements on the southern islands. Politically, Northern Canada refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. This area covers about 48 per cent of Canada’s total land area, but has less than 1 per cent of Canada’s population.

- The Canadian North is often subdivided into two distinct regions based on climate, the near north and the far north.

- The “near north” or sub-Arctic is mostly synonymous with the Canadian boreal forest, a large area of evergreen-dominated forests with a subarctic climate. This area has traditionally been home to the indigenous peoples of the Subarctic, that is the First Nations, who were hunters of moose, freshwater fishers and trappers. This region was heavily involved in the North American fur trade during its peak importance, and is home to many Métis people who originated in that trade.

- The “far north” is synonymous with the areas north of the tree line: the Barren Grounds and tundra. This area is home to the various sub-groups of the Inuit, a people unrelated to other indigenous peoples in Canada. These are people who have traditionally relied mostly on hunting marine animals and caribou, mainly barren-ground caribou, as well as fish and migratory birds.

Attachment #3: Greenland

- Although Greenland remains part of the Kingdom of Denmark, the island’s home-rule government is responsible for most domestic affairs. Home rule was granted to Greenland in 1979, though foreign policy and defence remain under Danish control. They call it an autonomous territory of Denmark.

- The Greenlandic people are primarily Inuit.

- The capital of Greenland is Nuuk (Godthåb).

- It is the largest island in the world. More than three times the size of Texas, Greenland extends about 1,660 miles (2,670 km) from north to south and more than 650 miles (1,050 km) from east to west at its widest point.

- Two-thirds of the island lies within the Arctic Circle, and the island’s northern extremity extends to within less than 500 miles (800 km) of the North Pole.

- Greenland is separated from Canada’s Ellesmere Island to the north by only 16 miles (26 km). Structurally, Greenland is an extension of the Canadian Shield, the rough plateau of the Canadian North that is made up of hard Precambrian rocks.

- Greenland’s major physical feature is its massive ice sheet, which is second only to Antarctica’s in size. The Greenland Ice Sheet has an average thickness of 5,000 feet (1,500 metres), reaches a maximum thickness of about 10,000 feet (3,000 metres), and covers more than 700,000 square miles (1,800,000 square km) – over four-fifths of Greenland’s total land area. It is a single ice sheet or glacier and the largest ice mass in the Northern Hemisphere.

- Layers of snow falling on its barren, windswept surface become compressed into ice layers, which constantly move outward to the peripheral glaciers. Most parts of the rock floor underlying the Greenland Ice Sheet are in fact at or slightly beneath current sea levels.

- Long, deep fjords reach far into both the east and west coasts of Greenland in complex systems, offering magnificent, if desolate, scenery.

- Along many parts of the coast, the ice sheet fronts directly on the sea, with large chunks breaking off the glaciers and sliding into the water as icebergs.

- On average, 473 icebergs per year manage to cross the 48° N parallel and enter the zone where they are a danger to shipping – though numbers vary greatly from year to year. Surviving bergs will have lost at least 85 percent of their original mass. They are fated to melt on the Grand Banks or when they reach the “cold wall,” or surface front, that separates the Labrador Current from the warm Gulf Stream between latitudes 40° and 44° N.

- Average annual precipitation decreases from more than 75 inches (1,900 mm) in the south to about 2 inches (50 mm) in the north. Large areas of the island can be classified as Arctic deserts because of their limited precipitation.

- Greenland’s vast ice sheet is shrinking at a highly increased rate.

- The country’s plant life is characterized mainly as tundra vegetation and consists of such plants as sedge and cotton grass. Plant-like lichens also are common. The limited ice-free areas are almost totally devoid of trees, although some dwarfed birch, willow, and alder scrub do manage to survive in sheltered valleys in the south.

- Several species of land mammals – including polar bears, musk oxen, reindeer, Arctic foxes, snow hares, ermines, and lemmings – can be found on the island. Seals and whales are found in the surrounding waters and were formerly the chief source of nourishment for the Greenlanders. Cod, salmon, flounder, and halibut are important saltwater fish, and the island’s rivers contain salmon and Arctic char.

This is so inspiring in photographs and script that I think I am going to be sick.

Simply amazing. I am not sure we were on the same trip….I learned so much reading this blog. Thank you for being so thorough. I loved your photos and thank you so very much for sharing this with everyone.

Ken and Penny – felt like I was experiencing this utterly awe-inspiring adventure with you Your camera lens captured exquisite visual scenes -breath-taking light and geological wonders. So much h fun seeing you both and some Stoney Lake friends. Thanks for the luring journal style. Betsy McGregor, Clear Lake

What a great treatise and information blog. Read with great interest. Seek a wider publication: Cdn Geographic?

Wonderful.

Thanx!!!!

Oh, Ken.

Thank you, thank you!

For your absolutely wonderful and detailed stories and photos of our expedition. I too have been writing and your blog has spurred me to keep going!

Best

Nancy

Ken and Penny,

You are amazing people, I will cherish all the memories, the talks, the giggles and in the quiet moments of such gratitude, to be able to travel in such magnificent beautiful places. I hope you stay in touch.

I am so glad you finally made this trip! Thank you for sharing thoughts and beautiful photos. Brings back wonderful memories of our trip in 2016!

Incredibly well done Ken. Your photography is breathtaking. Thank you for sharing your adventure. Too few Canadians experience and appreciate our north.

What and exceptional journey there are so few places in the world today that are left untouched and you were able to capture them in photos and with great insight and dialog.

Ken, this is a wonderful commentary of your fantastic adventure. The pictures are breathtaking and very interesting showing what the Arctic is really like……what anexperience for you both…..

Donna and Henry

It was great seeing you again. I hope we will have the chance to do so again in the near future.

Wonderful blog Ken –felt like I was with you.Thanks for sending it.

Brought back all the memories of a fishing trip John Martin, Jim King and I took to the High Arctic Lodge in July 99–base camp on Victoria Island.We flew around and

fished in many inlets and rivers while the pilot stood at the airplane with a rifle in

case a polar bear showed up.

Ken and Penny,

A trip of a lifetime. Your description and pictures bring it to life.

Hope you are both well and keep on tripping.

David and Bonnie

Ken, many thanks for sharing this fantastic adventure with us. Another Peterborough connection is that one of the marine archeologists who photoed the Franklin ships is the son of Piero & Gianna Ronca. Pete & Chick

Ken & Penny

Excellent description of a trip of a lifetime. What a wonderful part of our country so well documented. Thanks for sending this.

Carlo

Thank you so much Ken for this wonderful accounting of our trip. Knowing you and your camera were “recording” allowed me to really enjoy what I was seeing and experiencing without concern for record keeping. My iPhone camera didn’t stand a chance. It was, indeed – the trip of a lifetime!

Big hugs,

Gail

Thank you Ken! I spent several hours over the holidays re-living our trip. Your Blog and photos are, by far, the best and most complete record of the journey. Please let me know where your next adventure will be. If I am able to join in, I am certain I will be able to enjoy the adventure over and over again with what will be another outstanding collection of words and photos you will be sure to create.

Wonderfully descriptive, Ken…..and the photography was magnificent. Having spent more than half my life in the tropics, I’m not sure if I’m ready to include this one in my bucket list, but I’m tempted. Thank you.