(“Humour is just another defence against the universe.” Mel Brooks.)

Sitting in the choir boy seats, one of the early joys I relished when the twice daily chapel routine inflicted upon me during my six years of boarding school, was the possibility of being present during a real-time “spoonerism”. (This was separate from my reason for choosing to be in the choir, as it offered, as I would joke later, the practical benefit of LIFO, that inventory evaluation system, only known to accountants, as Last In, First Out.)

So to the “spoonerism” (which is an error in speech where vowels and consonants are switched between two words in a phrase). The affliction was named after a Reverend Spooner, Warden of New College in Oxford in the late 1800s, who was notoriously prone to this mistake. One savors “The Lord is a shoving leopard” instead of “The Lord is a loving shepherd.” These delights would pop out at unexpected times from the mouth of our esteemed school chaplain, and it certainly added humour to those dull, uninspiring moments.

As I enter the stage in my life that Shakespeare mordantly refers to in As You Like It, as “the last scene of all”, it seems clear that one of the essential traits to help proceed with “this strange eventful history” will be to retain and nurture ones sense of humour.

As the world continues to weary with COVID anxiety superimposed upon pervasive political and social tensions, I thought I’d take a break from past blogs and write on the elusive subject of humour.

E. B. White was quoted as saying “Analyzing humour is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it.” I intend, nevertheless, to take a crack at it.

You can read this blog in a number of ways: just contemplate the conclusions I have drawn at the end, or also read the rational I have crafted to reach these conclusions, or, as I hope some of you will do, dig into the attachments. In them there are some interesting gems. In particular, Attachment #6 is my attempt at identifying the amazing range of comic personalities that some of us have enjoyed over our lives.

Soon after I started, I found that the topic could not be dealt with casually. Some interesting and challenging questions needed to be addressed, like:

1. What is the history of humour?

2. Are there theories about laughter/humour?

3. Are there cultural distinctions and why?

4. Is humour different for different ages?

5. What are the different kinds of comedy/humour; skills and tools?

6. Can we tell something about a person’s character from their sense of humour?

7. What is the impact of humour on: a. Health/happiness; b. Wisdom; c. Prejudice?

8. What is the impact/role of humour on: a. Politics; b. Advertising?

9. How is humour now delivered/experienced?

10. What is the impact of technology on entertainers/humorists?

11. What has been the evolution of options as to where humour is performed and how it’s recognized?

12. Who were/are the important comedic personalities?

13. Can any useful/interesting conclusions re the expression of humour, whether professional or societal, be drawn from all this?

14. What conclusions can be drawn re the features/benefits of humour itself?

The dictionary can help us start. “Humour is the tendency of experiences to provoke laughter and provide amusement. The term derives from the humoral medicine of the ancient Greeks, which taught that the balance of fluids in the human body, known as humours, controlled human health and emotion.” There were four of these humours: blood, phlegm, yellow and black biIe. (I can understand blood, but the other three suggest the Greeks were into their wine.)

One of my very favourite comic writers is Dave Barry. When I was living in Miami in the mid 1980s, I faithfully read his humour column in the Miami Herald. Barry offered up his own definition of a sense of humour as “a measurement of the extent to which we realize that we are trapped in a world almost totally devoid of reason. Laughter is how we express the anxiety we feel at this knowledge.” It’s a clever definition, more now perhaps than ever before. (For a sampling of Barry’s humour search for his piece “A journey into my colon – and yours”. Try this: https://www.miamiherald.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/dave-barry/article1928847.html. Be prepared to be damaged from laughing.)

One other definition of comedy was proposed by P. G. Wodehouse in the preface to his collection of short humour pieces titled A Century of Humour (from the century 1830-1930). It goes “Comedy is a game played to throw reflections upon social life, and it deals with human nature…”

And finally, George Meredith, the English novelist and poet of the Victorian era, had this to say: “One excellent test of the civilization of a country … I take to be the flourishing of the Comic idea and Comedy, and the test of true Comedy is that it shall awaken thoughtful laughter.”

So the commonalities seem to be: laughter, happiness and entertainment; helping us navigate challenges and the absurdities of life; and dealing with human nature.

1. A Little Bit of History

To start, the the early history of comedy should be acknowledged. (Attachmhttps://powellponderings.com/category/life/ent #1: Early History of Satire and Comedy expands on this summary.)

The word “comedy” originated in Ancient Greece. In Athenian democracy the public opinion of voters was influenced by political satire performed by comic poets in theatres.

Aristophanes (446 – 386 BC) was a comic playwright and satirical author of the Ancient Greek Theatre where the three dramatic genres emerged, tragedy, comedy and then the satyr play. (These earlier satyr plays were often highly obscene.) Then Plato (424 – 348 BC) taught that comedy is a destruction to the self. He believed that it produces an emotion that overrides rational self-control and learning.

Thank goodness for Aristotle (384–322 BC), who while taught by Plato, opined that comedy was generally positive for society, since it brings forth happiness, which for Aristotle was the ideal state, the final goal in any activity.

Shakespeare (1564-1616) was a skilled comedic writer. Elizabethan audiences expected certain things when they went to the theatre. They wanted violence, they wanted a love story somewhere in the play, and above all they wanted to be entertained with humour. Shakespeare’s clever crafting would often use malapropisms and puns and slapstick.

A comedy of manners describes a genre of realistic, satirical comedy of the Restoration period (1660-1710) that questions and comments upon the manners and social conventions of a greatly sophisticated, artificial society.

Jesters and clowns are a cultural phenomena with a long history in many countries around the world. Jesters were members of a nobleman’s household and were paid entertainers. The comedy that clowns performed was usually that of a fool whose everyday actions become extraordinary – and for whom the ridiculous, for a short while, becomes ordinary. The Trickster in First Nations culture plays too the role of a crafty and cunning being that can cause mischief.

(Attachment #2: Jesters, the Circus, Clowns, and Tricksters expands on this.)

2. Are there theories about laughter/humour?

Academics and researchers get into the act trying to parse theories as to what is humour and why things are funny. They suggest the following:

– superiority theory: all humour is derived from the misfortunes of others – and thus our own relative superiority. (Slapstick humour, such as the pie-in-the-face or someone slipping on a banana peel, falls into this category.)

– relief theory: laughter lets us release energy/tension; a humorous scenario has some tension buildup, then release; this theory is the rationale behind the psychological/physiological benefits of laughter with the relief of tension leading to decreased stress, anxiety and even pain

– incongruity theory: posits that we find fundamentally incompatible concepts funny. It’s the juxtaposition of things that don’t normally go together (a talking dog?) This helps explain the appeal of jokes based on sex, ethnicity and religion. Resolving these incongruities can be humorous too

– benign violations theory: needs the presence of some sort of norm violation (moral, social, or physical) plus a benign or safe context in which the violation takes place, then the violation has to be interpreted as relatively harmless

– there is also a theory proposed by philosopher John Morreall that suggests the above theories are not mutually exclusive – that the common core to anything that prompts laughter is a “pleasant psychological shift”. The classic fart joke satisfies all of the above.

Some writers explore the concept of humour as a way of dealing with the absurdity of existence. In philosophy, “the Absurd” refers to the conflict between the human tendency to seek inherent value and meaning in life, and the human inability to find any in a purposeless, meaningless or chaotic and irrational universe.

3. Culture and humour; are there cultural distinctions and why?

While humour is universal, it can be culturally specific. To be practical, my emphasis in this blog is to English speaking humour. That starts off with my British/Irish heritage. What kind of literature makes them laugh? It might be a combination of P. G. Wodehouse’s sublime wit, a liberal dose of Joseph Heller’s black humour and a slice of Douglas Adams’ galactic comedy.

So the lists and references I have attached have a decided European/North American bent.

Do some cultures laugh more, have better (or different) senses of humour? Why, for example, do Newfoundlanders have that reputation? Sources are limited when one digs into cultures, but I’ll offer up some thoughts.

Citizens can be part of/buy into a national culture. The Oxford scholar, Theodore Zeldin said “The British have turned their sense of humour into a national virtue. It is odd, because through much of history, humour has been considered cheap, and laughter something for the lower orders. But British aristocrats didn’t care a damn about what people thought of them, so they made humour acceptable.”

The French love their language and a large part of their humour is based on it, which make it harder for non-French speakers to understand. They love puns, which are hard to follow unless you speak very good French. The French value wit (intellectual, hostile, aggressive, sarcastic, cynical) as opposed to Anglo-Saxon humour (for many – emotional, gentle, kindly, genial).

The French sense of humour is more oriented toward others than themselves, less nonsensical than English humour, more cruel and even mean. It is rarely self-deprecating: it is combative, fueled by ridicule and mockery and it needs a target. The French are great teases, which contribute (for naive foreigners) to their reputation of being rude. They love very earthy jokes about sex and bodily functions; you can hear them in the most unexpected contexts, like at a dinner table with well-educated people. Coluche, whose jokes were literally impossible to translate, was immensely popular.

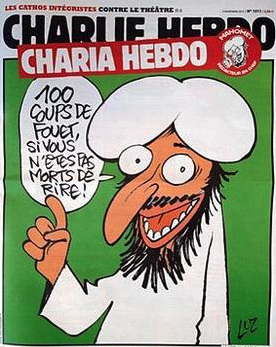

There can be huge cultural collisions with respect to humour. A dramatic example unfolded in 2015. Charlie Hebdo, a French satirical magazine, was having its weekly editorial meeting when two Islamic terrorists entered the room and killed almost everybody. Charlie Hebdo is a perfect example of the ultimate limits of French earthy humour. For the magazine editors nothing was deemed sacred; they believed in their right to laugh about anything to protect freedom of expression and therefore democracy.

When a Danish magazine published in 2005 a few caricatures of Muhammad (very mediocre, by the way), there was a surge of indignation and threats in the Islamic world. In France, people were not very interested but everybody, even the religious authorities, was shocked by the violence of the Muslim reactions. A few newspapers published some of the Danish caricatures, generating a flow of insults and death threats from the fundamentalist Islamist movements.

Charlie Hebdo made its cover with a drawing of a desperate Muhammad, looking like a very soft man, with his head in his hands and thinking “C’est triste d’être aimé par des cons” (“it is sad to be loved by assholes”) which infuriated the Islamists. From that moment, it became the main target of the Islamic terrorists, who finally succeeded in their killing spree. Islamic fundamentalists have no sense of humour; when unhappy, they kill.

There is some research on Western vs Eastern approaches and attitudes towards humour. It suggests that “Westerners regard humour as a desirable trait of an ideal self, associate humour with positivity, and stress the importance of humour in their daily life.”

It turns out that Easterners do not hold as positive an attitude towards humour as their Western counterparts. In China, there is a tug going on between different philosophies. On the one hand Confucianism devalues humour. Chinese self-actualization denigrates humour while stressing restrictions and seriousness. But on the other hand Taoism regards humour as “an attempt of having witty, peaceful and harmonious interaction with nature”.

This has resulted in an ambivalent attitude towards humour. “Even though Chinese might sometimes admit that humour is important in daily life, they do not think they are humorous themselves. For Chinese, humour is a talent that exclusively belongs to experts and is not a desirable trait of their ideal personality.”

Chinese are reluctant to admit they are humorous out of fear of jeopardizing their social status. There is some evidence that Chinese use humour in coping with “saving one’s face”.

Westerners see humour as an essential element of creativity; Chinese do not.

While some types of comedy were officially sanctioned during the rule of Mao Zedong, the Party-state’s approach towards humour was generally repressive. Social liberalization in the 1980s, commercialization of the cultural market in the 1990s, and the advent of the Internet have each – despite an invasive state-sponsored censorship apparatus – enabled new forms of humour to flourish in China in recent decades.

(Some of the above came from an Open Access Publisher article in Frontiers in Psychology by three professors at the University of Hong Kong and Peking University.)

4. Is humour different for different ages?

There are stages of development in children. Parents figure out what’s likely to amuse children at different stages.

– babies: don’t really understand humour, but they do know when a person is smiling and happy

– toddlers: appreciate physical humour, especially the kind with an element of surprise. It’s around this time that many kids start trying to make their parents laugh

– preschooler: is more likely to find humour in a picture with something out of whack than a joke or pun. Incongruity between pictures and sounds is also funny

– school-age kids: as kids move into kindergarten and beyond, basic wordplay, exaggeration, and slapstick will all be increasingly funny

– older grade-schoolers: have a better grasp of what words mean and are able to play with them – they like puns, riddles, and other forms of wordplay. But kids this age are also developing more subtle understandings of humour, including the ability to use wit or sarcasm and to handle adverse situations using humour

(For an expanded account of these skills see Attachment #3: Different ages – different humour)

5. What are the different kinds of comedy/humour; skills and tools?

Comedy may be divided into multiple genres based on the source of humour, the method of delivery, and the context in which it is delivered. In the performance world it can take the form of observational, sketch, stand-up, and improvisational comedy; it can use satire, parody, novelty songs, practical jokes and pranks. Humour can also be self-deprecating, bodily function oriented; surreal; black; blue/ribald or insult.

Regarding pranks, to illustrate, when I was young I used to be a bloody nuisance at family dinner parties, as I had a collection of “things that I thought were amusing” and would put them into play, such as whoopee cushions, devices that would raise dinner plates across the table, fake ice cubes with bugs inside them. I even had cigarettes that would stink or explode when lit. All quite charming.

For expanded definitions see Attachment #4: Kinds of comedy/humour; skills and tools.

6. Can we tell something about a person’s character from their sense of humour?

We all enjoy a good laugh, but not all of us find the same things funny. Everyone has a unique brand of humour that is special to them. “What does your sense of humour say about you?” Can you tell something about a person from the jokes they make, the comedy they laugh at, and their ear for a good, funny anecdote? It is said that nothing shows man’s character more than what he laughs at.

How do you classify yourself – the big, obvious belly-laugh type or the subtle, sly, understated dry version? I myself am a complicated amalgam of both; my father a Brit, was understated and dry; my mother with her Irish background was more outrageous and extraverted.

To survive at boarding school (and any other institution, I might add, be it camp, a job, a club) one needs to develop certain coping mechanisms. Humour and practical jokes are one way. New boys at my boarding school were instructed to report to the nurse “to get their mouth measured for a soup spoon”; “wedgies” and “sunflowers” were inflicted; institutional food labelled creatively (“mystery” pie anyone? Or as the chapter title on food of an amusing book on boarding schools read, “The piece of cod which passeth all understanding”). Teachers were nicknamed: “Fingers” Fenson, “Clank” Staples”, “Mad Jack” Matheson, “Wally Woo” Wykes, “Beakie” Hanna and “Nippy Jim” Pringle. This is only the start.

The short answer to my question at the beginning of this section is, yes we can tell something about people from their sense of humour. According to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), our views on the world, and even our comedic appreciation, is directly linked to how we perceive the things around us. Carl Jung laid the groundwork for the Myers-Briggs test, but much of the test was developed by Katharine Briggs and Isabel Myers.

The theory went that all human beings experience the world according to four main psychological states: sensation, intuition, feeling, and thinking. Furthermore, one of these four is dominant in a person’s life most of the time. The personality types are varying examples of introversion and extroversion creating eight dominant functions. So we have 16 variations. For a description of these definitions see Attachment #5: Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.

There are different styles of humour that each personality type possesses. I have been defined as ENTJ. Humour for this group is defined as follows: “ENTJs can have a somewhat outrageous sense of humour. They enjoy pushing the envelope to gauge the different reactions they will receive from others. They aren’t afraid of being seen as ridiculous, so they often push the limits of what others may perceive as funny. They are often very quick with wit and can respond to people before they even realize a joke is coming.” There is more, but that’s enough.

While the MBTI has some flaws, it is useful for self-reflection. It can be a starting point for discussing how people vary in their personalities, and emphasizing tolerance for individual differences and taking others’ perspectives.

Recent research on humour now views it as a character strength. Humour can be used to make others feel good, to bond with people, to gain intimacy or to help buffer stress. Having a sense of humour helps us forge connections to the world and provide meaning to life.

7. What is the impact of humour on: a. Health/happiness; b. Wisdom; c. Prejudice?

a. On health and happiness: “Laughter is the best medicine” may have some credence. Studies show that people who laugh more often get sick less. Researchers from Finland and the United Kingdom have found that social laughter triggers the release of endorphins – often referred to as “feel good hormones” – in brain regions responsible for arousal and emotion. As reported in The Journal of Neuroscience the study co-author Prof. Lauri Nummenmaa, of the Turku PET Centre at the University of Turku in Finland, said “Our results highlight that endorphin release induced by social laughter may be an important pathway that supports formation, reinforcement, and maintenance of social bonds between humans.”

Research has shown that people who laugh more are healthier – they’re less likely to be depressed and may even have an increased resistance to illness or physical problems. They experience less stress; have lower heart rates, pulses, and blood pressures, and have better digestion.

Laughter may even help humans better endure pain, and studies have shown that it improves our immune function. A sense of humour is what makes life fun. Humour is social. That’s why you laugh harder at a funny movie when you see it in the theatre with other people laughing around you, than all alone on your couch.

Humour is in the now, but younger people tend to think about things in the future (“won’t it be great when…”) and older people with the past (“wasn’t it great when…”). Entire religions have been constructed from the past joys (when things were great in the Garden of Eden) or future joys with eternal happiness in a Heaven, Valhalla, Hannah or Vaikuntha. There is also a natural inclination to think positively about the future, with self-deception enabling us to keep striving.

b. On wisdom: wisdom is a form of reasoning that increases with age and is correlated with subjective well-being. Humour is linked with wisdom – a wise person knows how to use humour or when to laugh at oneself. Research is taking place regarding how individuals seek humour in their daily lives; early results suggest those high in humour character strength tend to concentrate on the positive aspects of their past, present and future. Those who seek humour in their lives appear in the study sample also to focus on the pleasant aspects of their current lives.

c. On prejudice: a growing body of research suggests that attempts to amuse through the denigration of a social group through racist or sexist jokes (disparagement humour) can foster discrimination. Researchers in the 1970s studied the TV show “All in the Family”, which focused on the bigoted character Archie Bunker. They found that low-prejudiced people perceived the show as a satire on bigotry and that Archie was the target of the humour. They “got” the true subversive intent of the show. In contrast, high-prejudiced people enjoyed the show for satirizing the targets of Archie’s prejudice. For them, the subversive disparagement humour backfired. The character of Archie was so well written and well played by the actor Carroll O’Connor that many saw it as finally giving voice to their values into prime time. Archie was not taken as being sardonically humorous, but as authentically reflective.

8. What is the impact/role of humour in: a. Politics; b. Advertising?

a. In politics:

Recently there has been a smattering of comedians taking a shot at politics. Jon Gnarr invented a new party when running for mayor of Reykjavik, calling it The Best Party (he was helped by the fact that Icelandic people have a very dark sense of humour). He got elected. Three other recent examples suggest the voting rabble are interested in the possibilities. VolodymyrZelensky, acomedian, has been serving as the current president of Ukraine since 2019. Marjan Šarec, alsoa comedian has served as the PM of Slovenia from 2018 to 2020. Jimmy Morales, an actor and comedian, served as the president of Guatemala (2016- 2020).

One of my favourite Canadian examples is a man who aspired to be Prime Minister, but was unsuccessful – the Newfoundland-born John Crosby. He was a very bright and witty politician. I attended the 1983 leadership convention in Ottawa. At the convention Crosby placed third behind Brian Mulroney and Joe Clark. While it was evident at the event that Crosby was the most popular of the candidates and his sense of humour beguiled the attendees, he lost, doomed by his inability to speak French. It would have been a refreshing experience to have him lead our country.

Comedians have attempted to use their profile to effect political change. In the US, a Washington tradition has been the White House Correspondents’ Association (WHCA) annual dinner. Since 1983, the featured speaker has usually been a comedian, with the dinner taking on the form of a comedy roast of the president and his administration. Stephen Colbert was the featured entertainer for the 2006 White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner. Standing a few yards from President George W. Bush, in front of an audience of the “Who’s Who of power ”, Colbert delivered a searing routine targeting the president and the media.

Here’s a sample of his remarks; this part in regard to the lead up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, “But, listen, let’s review the rules. Here’s how it works. The President makes decisions. He’s the decider. The press secretary announces those decisions, and you people of the press type those decisions down. Make, announce, type. Just put ’em through a spell check and go home. Get to know your family again. Make love to your wife. Write that novel you got kicking around in your head. You know, the one about the intrepid Washington reporter with the courage to stand up to the administration? You know, fiction.” Acerbic, cutting, funny.

The video of his performance became an internet and media sensation (while, in the week following the speech, ratings for The Colbert Report rose by 37%!) The New York Times called it the “defining moment” of the 2006 midterm elections.

In communist China, does President Xi Jinping smile; have we any sense of whether he or any of his comrades have any kind of sense of humour? François Bougon’s book “Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping” suggests that Xi’s seven years spent as a “sent-down youth” farming in Yanan with the peasants has formed him in a serious way. “Xi is deeply troubled that the same spirit of self-denial and sacrifice that was instilled in him at Yanan is missing from later generations of party members.” President Xi said during a 1995 interview, “My seven years of rural life …gave me something mysterious and sacred.”

Xi’s experience may be more revealing than that of President Donald Trump. Certainly one of Trump’s significant personality flaws, deemed by many, is his incapability to sense and use humour.

b. In advertising:

Humour is often used to sell products or services. There are so many examples. A recent one is a commercial for Wrigley’s EXTRA brand gum entitled “For When It’s Time” showing the behaviour of people once they find the pandemic is over. It’s 2 1/2 minutes of just images (guy running through kitchen past a huge stack of toilet paper rolls, a girl rising out of bed covered in pizza cartons, etc.). All of this with Céline Dion singing “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” and the actors chewing the product. It is an excellent example of advertising using humour to effectively promote a product. (See: https://nypost.com/2021/05/10/why-are-people-getting-choked-up-at-this-ad-for-gum/)

9. How is humour now delivered/experienced?

Humour is found and delivered in many direct and indirect ways through four broad categories:

– simple personal social interaction as part of a conversation, individually or in groups (a joke told while playing golf or a typical Newfoundlander kitchen party, for example)

– the performance world, through the spoken word or gestures or mime or ventriloquism via plays, circuses, speeches, radio, television, in comic clubs or bars and the Internet

– the written word (non-verbal): through books, magazines, the Internet (again) with stories, poems, limericks, etc.

– visually in a graphic sense through movies, cartoons, comics, animated sitcoms

10. What is the impact of technology on entertainers/humorists?

Two significant technological developments happened almost at the same time in the late 1800s that affected the role of entertainers. The first was around 1885 when it became possible to record sound. This eventually morphed into many possibilities, and certainly the record/tape/DVD business.

The second, within ten years, was that the movie camera became a practical reality. Initially there was little cinematic technique, the film was black and white and it was without sound. The motion picture industry then blossomed in countries around the world. “The Cinema” offered a relatively cheap and simple way of providing entertainment to the masses. The first successful permanent theatre showing nothing but films was “The Nickelodeon”, which was opened in Pittsburgh in 1905. Within two years, there were 8,000 of these nickelodeons in operation across the United States. The American experience led to a worldwide boom in the production and exhibition of films from 1906 onwards.

By 1907, purpose-built cinemas for motion pictures were being opened across the United States, Britain and France. The films were often shown with the accompaniment of music provided by pianists.

The challenge of synchronizing a sound recording with the film was eventually solved in 1927, and silent film became talkies.

The consequence was a profound change for entertainers. Instead of plays and one-off performances to relatively small audiences, the entertainer, whether actor, comedian, mime or whatever, could reach a broad audience, multiple times, at any time.

Regarding the written word, the invention of the printing press in 1440 and the steam powered rotary press in 1843 permitted the printing of words and the mass distribution of books, newspapers, magazines, etc. It’s now not necessary to count on some Bedouin shepherd to unearth a one-off Dead Sea Scroll.

11. What has been the evolution of options as to where humour is performed (and how it’s recognized)?

From the Victorian Music Hall in the UK and vaudeville in America through to radio, to TV, to animated, to the unconstrained world of the Internet and social media, a continuous development has occurred in the presentation of comedy. Most of the early top performers on British radio and TV did an apprenticeship in stage variety shows. In the US, former vaudeville performers such as the Marx Brothers, George Burns and Gracie Allen, W. C. Fields and Jack Benny, honed their skills in the Borscht Belt (popular vacation spots for New York City Jews from the 1920s through the 1960s) before moving to talkies, to radio shows, and then to TV shows, including the ubiquitous variety show.

Radio comedy began in the United States in 1930, and got a much later start in the United Kingdom because many of the British comedians (such as Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel) emigrated to the US to make silent movies in Hollywood. Radio variety shows were the predominant form of light entertainment during the Golden Age of Radio from the late 1920s through the 1940s; such radio shows typically included a stand-up monologue and a short comedy sketch.

Even after the big name comedians moved to television in the Golden Age of TV (roughly from the late 1940s through the late 1950s), radio comedy continued, notably from Bob and Ray (1946-1988), The Firesign Theatre (1966-1972), and segments heard on NBC’s Monitor (1955-1975).

Variety shows continued to be produced in the 1970s, with most of them stripped down to only music and comedy. By the 21st century, the variety show format had fallen out of fashion, due largely to changing tastes and the fracturing of media audiences (caused by the proliferation of cable and satellite TV) that makes a multiple-genre variety show impractical.

The advent of cinema in the late 19th century, and later radio and TV in the 20th century broadened the access of comedians to the general public. In America the Ziegfield Follies, Jack Benny Show, Colgate Comedy Hour, Laugh-In, Saturday Night Live drove us through the 1930s, 40s and on into television. This was followed by series like MASH, Seinfeld and The Simpsons.

In the UK there was initially The Goon Show of the 1950s with its ludicrous plots and surreal humour followed by Beyond the Fringe in the early 1960s, through to Faulty Towers and then the wonderful Monty Python gang.

Starting from the late 1950s awards for humour in the US commenced. Emphasizing TV comedy and comedy films, the American Comedy Awards were a group of awards presented annually recognizing performances and performers in the field of comedy. They began in 1987, billed as the “first awards show to honor all forms of comedy.” In 1989, after the death of Lucille Ball, the statue was named “the Lucy” to honour the comic legend. The awards ceased after 2001 but they served important focal points. For comedy albums, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences of the US offer an award for Best Comedy Album to “honor artistic achievement in comedy.”

The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor is an American award presented by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts annually since 1998. Named after the 19th-century humorist Mark Twain, it is presented to individuals who have “had an impact on American society in ways similar to” Twain.

There are annual awards celebrating Canadian comedians for achievements in live, TV, film, radio and web comedy. An annual national awards ceremony, the Canadian Comedy Awards, are for quite a range of possibilities – best artist, feature, short, comedy album, writing, live performance, stand-up comic, TV show, web series, etc.

12. Who are the important comedic/humorous personalities?

It was great fun while researching this subject to remind myself of the comedic personalities I have read, watched or listened to in my lifetime, and who I really thought had merit and were funny. They range from writers and cartoonists, to the performance types (actors, stand-up comedians, clowns, etc.). There should also be a category listing my amusing friends.

Those who pursued their craft in the professions of acting and performing at a high profile level are a colourful and talented lot. America has produced a great number of globally renowned comedy artists. Smiles come to my face when I recall (and I am old enough to say this) such names as Charlie Chaplin, Sophie Tucker, Groucho Marx, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, Burns and Allen, Mae West, Jimmy Durante, Jack Benny, George Jessel, Bob Hope, Abbott and Costello, the Three Stooges, Edgar Bergen, Milton Berle, Danny Kaye, Red Skelton, Red Buttons, Shelly Berman, Jack Lemmon, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Mel Brooks, Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, Lucille Ball, Jackie Gleason, Art Carney, Phyllis Diller, Andy Rooney, Rodney Dangerfield, Don Adams, Don Rickles, Tom Lehrer, Carol Burnett, Lenny Bruce, George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Joan Rivers, Woody Allen, Jack Nicholson, the Smothers Brothers, Steve Allen, Lilly Tomlin, Goldie Hawn, Bob Newhart, Whoopi Goldberg, Gilda Radner, Eddie Murphy, Robin Williams – and that’s only a sampling on the American side and doesn’t touch recent talent.

On the British/Irish side we have George Formby, Benny Hill, Peter Sellers, Dudley Moore, Peter Cook, John Cleese, Dave Allen, David Frost, Rowan Atkinson, Brendan O’Carroll and Sacha Baron Cohen.

The Canadian comics are likewise memorable: Beatrice Lilly, Mort Sahl, Wayne and Shuster, Rich Little, Martin Short, John Candy, Rick Moranis, Dave Thomas, Catherine O’Hara, Howie Mandel, Colin Mochrie, Jim Carrey, Mike Mayers, Stuart McLean, Mary Walsh, Samantha Bee, Rick Mercer and Steve Patterson. Internationally, there are a few to recall: Victor Borg, Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan.

A little known fact is that while Jews make up about 2% of the US population, there was a time they made up 50% of the famous comedians. Going forward from the days of Groucho Marx we have: George Burns, Jack Benny, George Jessel, the Three Stooges, Henny Youngman, Milton Berle, Danny Kaye, Phil Silvers, Jan Murray, Red Buttons, Jack Carter, Jack Sherman, Shelly Berman, Jerry Lewis, Shecky Greene, Mel Brooks, Buddy Hackett, Sid Caesar, Joey Bishop, Rodney Dangerfield, Don Rickles, Mort Sahl, Jackie Mason, Lenny Bruce, Totie Fields, Woody Allen and Howie Mandel.

The Irish are wonderful at telling stories, often with dry, biting sometimes sarcastic wit. As the Jews, they are over-represented as comedians to population. Brendan Behan once remarked, “Other people have a nationality. The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.”

While comedy is not a gender equal industry, it has over the years produced some leading female icons. Some powerful and entertaining female comedians entered the scene early and made for a formidable lot: Sophie Tucker, Eva Tanguay, Fanny Brice, Beatrice Lilly, Gracie Allen, Mae West, Judy Canova, Kathleen Freeman and Imogene Coca.

Following these pace-setters from the late 1950s, this powerful, but small, group of female personalities was followed by an increasingly strong cadre of performers to carry on the tradition: Elaine May, Lucille Ball, Phyllis Diller, Carol Burnett, Joan Rivers, Ellen DeGeneres, Goldie Hawn, Ruth Buzzi, Lilly Tomlin, Gilda Radner, Whoopi Goldberg, Tina Fey, Roseanne Barr, Rita Rudner, Catherine O’Hara, Elayne Boosier, Totie Fields, Mary Walsh, Amy Poehler, Samantha Bee, Kathleen Madigan.

Along with those memories go the crazy gimmicks or lines for which they became known. Some of my favourites example include: Gracie Allen’s “illogical logic”; Durante’s “SchnozzoIa”; Bennys’ being a “miser”; Hope’s calculated pauses; Abbott & Costello’s routine “Who’s on first”; Dean Martin as a drunken playboy; Gleason’s “Awaaaay we go”: Tim Conway’s shuffling old man with the white wig; Tommy Smothers’ “Mom always liked you best”; Ruth Buzzbi’s dowdy spinster with her hairnet; Arte Johnson falling over riding his tricycle; Lilly Tomlin’s telephone operator character saying “one ring dingy, two ringy dingy”; Tina Fey’s satirical portrait of Sarah Palin; Carlin’s “seven dirty words”.

I have attempted to capture the characters and their antics in Attachment #6: Important Stage and Screen Personalities and Venues in the Comedic World of the Recent Past. It lists 146 men and women who can be used to track the art and profession over the past century and 28 venues or programs that have served as platforms for these people (England, US, Canada and internationally). I have also identified 16 influential late-night talk show hosts.

The world of writing funny stuff is extraordinarily broad, so again selecting examples is risky. Nevertheless I have selected a few writers that have amused me, starting off with the king of limericks, Edward Lear and continuing with Mark Twain, Stephen Leacock. P. G. Wodehouse, E. B. White, Ogden Nash, the great Irish satirist and wit Brendan Behan (along with two other great Irish wits, George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde), Art Buchwald, Emma Bombeck, Neil Simon, Bill Bryson and Canadians Terry Fallis and a friend of mine Charley Gordon. See Attachment #7: Comedy/Humour Writers.

Cartoonists (and the comic book genre) deserve special mention, so I’ve selected those who I think have been influential, some 18 in total, including Thurber, and the talent behind Blondie, Dr. Seuss, Giles, Peanuts, Herman, Garfield, For Better or For Worse, The Far Side and Maxine. While there are more and more cartoonists, there is less space being set aside for them in newspapers. There used to be large “comic” sections, or at the very least, a full page. See Attachment #8: Influential Cartoonists.

13. Conclusions re the expression of humour, whether professional or societal

- There are distinctions from culture to culture regarding how humour is expressed, interpreted and considered, but humour, like music, is embedded in our social structure

- The “profession” of comic (performance, writing, drawing, animated) goes back more than 2,000 years. But it has gained commercial significance in the past 100 years, and even greater impact in the past 50

- In those past 100 year the journey from real-time theatre and club environment, to radio, to TV, to the unconstrained world of the Internet and social media has been one of rapid expansion

- Humour is now big business, from a comic performance standpoint (radio, TV, comedy clubs, etc.), to the humorist writing and graphic methods (books, magazines, comics and cartoons, billboards, bumper stickers, Internet, blogs, etc.)

- Comedy has been dramatically expanded and democratized through technology (printing presses permit the mass distribution of the written word; sound and film/tape equipment now record, distribute and preserve performances)

- There are many more ways to bring humour into the world today, whether through the written or spoken word, or through performers, be they actors, clowns, mimes, etc. and through the mediums that are used

- Over the years certain groups and forums have played an important role in providing a forum for launching careers or displaying talent. In Britain the music hall began it all; then came the Goon Show in the 1950s followed by Beyond the Fringe in the early 1960s. From from 1969 to 1974 the sketch comedy troupe, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, launched important players

- In the US, vaudeville (from the 1880s to the 1930s), along with Ziegfeld Follies, launched the careers of some iconic talent (Will Rogers, W. C. Fields, Charlie Chaplin, Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice). Then radio and the television screen provided platforms from which famous careers were launched, e.g. Matinee, The Colgate Comedy Hour, Monitor radio program, Firesign Theatre, Laugh-In, Saturday Night Live, The Improv comedy club franchise, Comedy Central

- Late-night talk shows became a phenomenon (unlikely as they seemed at the time), starting with Steve Allen and Jack Paar in the 1950s and 1960s through to Johny Carson, Dick Cavett, Merv Griffin, Jay Leno and David Letterman in the 1960s, 70s, 80s (and more) all feeding the current talent (Joan Rivers, Conan O’Brien, Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, etc.)

- Over the years of radio, then TV, a specially durable group of comedians have had particularly long careers performing live in front of audiences decade after decade. They are of note: Will Rogers, Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, Burns and Allen, Durante, Benny, Hope, Berle, Skelton, Caesar, Gleason, Burnett, Woody Allen and Nicholson

- The writing of humour, whether for magazines or books, has exploded as a genre from the early days of P.G. Wodehouse, Mark Twain, and Steven Leacock

- Female comedians have played an outsized role in the delivery and maturation of, particularly performance, comedy

- Jewish comics in the US have played a significant role in the comedic world

- Irish comedians are over represented in the field

- Cartoonists play an influential role in culture and especially politics

- The life of a performance comedian is not an easy one, and not always funny. When digging through the personal lives of the comedians, tragic patterns emerge – many were into their third and more marriages; as well alcohol and drugs played an oversized role. Robin Williams perhaps put his finger on it from the life of a stand-up comedian, “It’s a brutal field, man. They burn out. It takes its toll. Plus, the lifestyle – partying, drinking, drugs. If you’re on the road, it’s even more brutal.”

14. Conclusions re the features/benefits of humour itself

- Humour, in the Western world, is an essential component of the human condition, as much as sadness, pathos, anger. (It can be likened to music in importance as part of he human social structure.)

- Humour is social. Laughing together is a way to connect, to share. It is a bonding agent. It can also be very contagious, with one thought/comment triggering more and more laughter

- Humour as a communications tool can be effective; jokes, aphorisms and pithy sayings communicate extraordinarily well. Humour can break tension, indicate understanding of an audience, and show tolerance for other perspectives

- Humour is healthy: it is an anesthetic for pain, reduces physical and mental sickness, and stress; it is cathartic

- Humour can be cultivated and encouraged in children; a good sense of humour can make kids smarter, healthier, and better able to cope with challenges

- Humour plays an impact in politics through the influence of wit and sarcasm in political debate. A clever political cartoon can influence the public in a simple graphic fashion; a potent wit in political debate produces large returns

- Humour can be vehement, vicious, and in your face – to make a point. Witness the Charlie Hebdo caricatures resulting in such a violent response

- Indeed humour can be used for negative purposes. The deeds of a sword lie in the hand of the wielder

- When used cleverly, humour sells (products, services, issues)

- Humour is found everywhere, morphing from traditional sources (verbal/performance and written/drawn channels) into unconventional channels (the world of subscriber TV, the Internet, podcasts, blogs; it even hits billboards and church roadway signs)

- It seems likely the Internet has changed how we exchange humour. People related many more jokes a few years ago. Now, as jokes come at us with great rapidity over the internet, the one-on-one verbal exchange seems diminished

- There is a fine line between fake news and satire. Sometimes being inside a cultural group (for example First Nations) is the only way to be part of the humour or to understand it. When oppressed or under difficult situations, humour is used as a relief valve, an escape, for adapting, or even surviving

- The level of acceptance/tolerance for off-colour (or sarcasm or just rudeness) has escalated significantly. In the 1967 compilation of “The Wit and Wisdom of Mae West”, she was purported to say “Is that a gun in your pocket, or are you just glad to see me?”. She was universally condemned. Fast forward to Lenny Bruce in the 1970s moving the markers; now there is a wide tolerance, except…

- Jokes with discriminatory content are verboten, e.g. Jewish, Polish, Black, Newfie, etc. are off limits. Some clever artists can run against this, but with purpose. A LGBTQ humour market is also emerging

- Humour appears to have cultural distinctions. At the risk of being too simple, the British have turned their sense of humour into a national virtue; the French love their language and a large part of their humour is based on it; the Chinese have an ambivalent attitude towards humour. Generally Westerners regard humour as a desirable trait, associate humour with positivity, and stress the importance of humour in their daily life

- Humour may serve a philosophical role for many. Albert Camus writes about embracing the absurd condition of life through “passion”, which for him refers to the most wholehearted experiencing of life; he concludes that every moment must be lived fully. Perhaps humour helps in achieving this end

Post Script

Writing this blog on humour reinforces for me the attraction of writing in the first place. It’s not just the challenge of arranging information in a logical sequence, sorting the important from the inconsequential and then extracting relevant conclusions or lessons. The joy really is in the process – the reading and thinking that precedes the writing – that’s all the fun.

For example this subject of humour has taken me into my library (another argument for having such a place) where I have found myself reading (rereading) such things as Sophocles and Plato; The Best Laid Plans by Terry Fallis; a grand old book entitled A Century of Humour edited by P. G. Wodehouse and published in 1934; The Lure of the Limerick: “an uninhibited history”, dated 1963; Charley Gordon’s At the Cottage, and so on. I poked through The Canterbury Tales and some Shakespeare. A good friend of mine also brought over a few of his old cartoon books (The Far Side, Herman, etc.)

The internet disgorged excellent material on a whole range of comedians, comics, and many other subjects (thank you Wikipedia, Encyclopedia Britannica, etc.). I found in my own extensive filing system, information on Myers-Briggs (the management team at Imperial Oil had taken the tests), plus a large file on jokes and anecdotes people had sent me over the years. The whole process was just a lot of fun, and challenging and took me down many rabbit holes. The input/output ratio was low but the input/interest ratio was quite high.

I failed to see any mention of Stephen Leacock’s Essay on Humour.

Good work Kenny, Yes, it’s a diverse & complex topic on which you laid groundwork for students to further advance the topic.

Bill H

Got to read that Bill; good suggestion. The subject kept growing on me – so my usual dilemma was when to stop digging and adding! Ken

Way go! If you were my student, I would give you an A+ on your philosophical essay on “humour”. Keep going; You are getting younger.

Claude

Ps. Althow I only read the first 2/3 of your document, I was surprised not to have references on the natives people reference I was surprised not to have you question. As ears humour was very present and distinguished among the various native groups.

Thanks Prof; I’ll take your compliments! I have done some reading on native humour, and it’s there, of course, and in some ways it can talk to some of the social issues they face. But it’s tricky; sometimes it makes people sad and not laugh. This could be tackled but like a lot of the angles on humour, it’s a continuing expansion on the blog. Already my blogs tend to be long, so I’m constantly battling this issue. (That’s why I put a lot in the attachments, where people can dig around for a broader view.) If there is a succinct way to handle it, I’ll look at it. Ken

Very thorough, as usual, Ken. There are gender differences as well, I believe, re what tickles one’s funny bone. Early life experiences and family dynamics play a big role – you tackled a huge topic and are likely still exploring it.

As a recreational golfer, you may wish to read “Albatross” by Terry Fallis, though you may already have done so.

I think Fallis is a funny guy, but I haven’t read Albatross; thanks, I’ll get it. (Anything about golf just has to be funny.) BTW I met Fallis right after he wrote his first book and couldn’t get a publisher. So he used a self publishing firm and it was he who recommended that company (called iUniverse) to use when I published my autobiography. When Best Laid Plans went on to win the Leacock prize, of course then McClelland & Stewart quickly picked him up.

Ahh, my good (and humorous) friend, you have done it again with another thought provoking blog. I realize I never responded to your previous blog after saying that I would, maybe because I found it much too serious (and not very funny), but this blog just begs a reply which I have already started.

In the meantime I can’t help reflect on the occasions we meet for lunch with Don . . . and realized that a predominance is each looking for the funny memory to share and rehash with smiles and laughs, often centering on one of us but also on the many characters (should we say “funny characters”) we have collectively or individually met. So perhaps an additional conclusion to add is . . . humour is a bond. (And of course, that’s the Canadian spelling of “humour” and not the one this spellcheck would have me pick.)

Take care

Ed

I think you make an excellent point about humour being sort of a bond between people. I’m going to add that idea to my conclusions. Thanks. And so, I look forward to our next opportunity to laugh together!